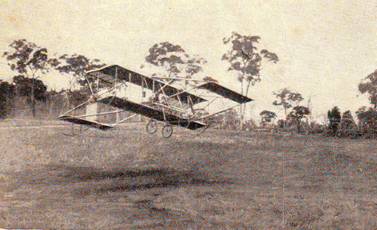

This gives a good idea of takeoff. Uncle Jack with cap pulled well down leaning forward to help the engine, right hand on the elevator stick just about to level her off, left hand on the aileron stick picking up the port wing. Since the ailerons were not interconnected, the idling pair would give a good idea of the aircraft’s true path through the air. In this case the right hand bottom one can be seen parallel to the lower chord of the tail plane, showing the machine is flying pretty well as it is pointing, although the downswing of the wing would modify this slightly.

The propeller seems to be bending well forward, although this may be the effect of the focal plane shutter. On second thoughts, this effect would always give an apparent bend in the opposite direction.

Both Duigans were experienced photographers and did their own developing and printing but Father took most of the early photos of the plane, because Uncle Jack stuck to the helm of the plane while he was still experimenting.

The technique generally adopted was, for Father to start the engine then run ahead for say a hundred yards, [ten seconds overheating made the pilot restless to be on his way], and then snap the machine as it went past. It would then fly up to the top of the paddock, land and simmer down. It would then turn round and the process repeated if there wasn’t too much wind. Speed was measured roughly by timing takeoff to touch down and making calculations. The brothers had an anemometer, but never attempted to take it in the air.

The propeller seems to be bending well forward, although this may be the effect of the focal plane shutter. On second thoughts, this effect would always give an apparent bend in the opposite direction.

Both Duigans were experienced photographers and did their own developing and printing but Father took most of the early photos of the plane, because Uncle Jack stuck to the helm of the plane while he was still experimenting.

The technique generally adopted was, for Father to start the engine then run ahead for say a hundred yards, [ten seconds overheating made the pilot restless to be on his way], and then snap the machine as it went past. It would then fly up to the top of the paddock, land and simmer down. It would then turn round and the process repeated if there wasn’t too much wind. Speed was measured roughly by timing takeoff to touch down and making calculations. The brothers had an anemometer, but never attempted to take it in the air.

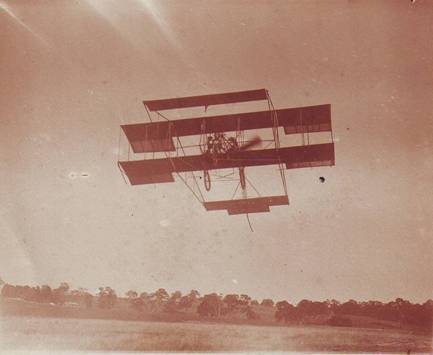

Plane climbing

The Duigan 1910 Pusher coming in to land.

This has the look of coming in to land about it, with the elevator heavily down, and it should be, because the halfway bend is off to the right in the distance, so the aircraft should be approaching the last quarter of the field. It is still making a right hand turn, and the trailing wheels are acting like turn and bank indicators and showing the amount of skid. The banked turn, of course, was unheard of, although it was beginning to appear in Europe at this time.

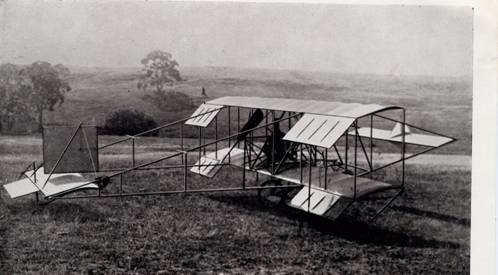

The 1910 Duigan pusher at "Spring Plains"

By the beginning if 1911 the machine was reaching the limit of its development with its present engine. Father was allowed to fly it; previous restriction had probably been made as much for his sake as for the plane’s, although he doesn’t see it that way and had no difficulty in making flights of up to half a mile or so. Although he got the impression that he was all over the sky, he was, in fact, flying quite steadily. The machine responded slowly to the controls and lost height if they were used coarsely, however it would take off in a few yards into a breeze, and climb to fifty or sixty feet in the length of the field. It would fly straight and level, hands off, at about 45 m.p.h. Now only the lack of a suitable ground prevented the evolution of manoeuvres.

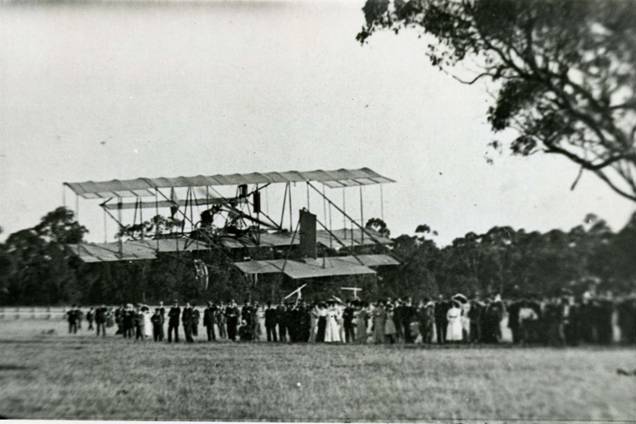

Duigan Aeroplane flying over Bendigo Racecourse, May, 1911

In March 1911, the aeroplane was taken to the Show Grounds at Bendigo, where it was found that the ground was far too small, even hops were impossible. As an afterthought and to make money for charity, it was decided to fly it on the racecourse. [after it had been stripped down for transport home]. It was quickly reassembled, thanks to the detachable wing tips, and for the first time, Uncle Jack had the use of comparatively unrestricted ground. He made a number of flights of up to three quarters of a mile and this picture shows the publics confidence in his ability to control his steed. He appears to be edging away from the crowd in a climbing turn, because for once the ailerons on the dropped wing are down. Probably a day or two on this ground and he would have been doing banked turns.

The machine was returned to Spring plains. The final events in its active life were demonstrations before the Defense Authorities and the Aerial League of Australia. On May the 31, 1911, it metaphorically hung up its football boots.

Uncle Jack had now definitely elected for aviation and realizing that he was too isolated to be more than a mere curiosity where he was, he immediately left for England.

The machine was returned to Spring plains. The final events in its active life were demonstrations before the Defense Authorities and the Aerial League of Australia. On May the 31, 1911, it metaphorically hung up its football boots.

Uncle Jack had now definitely elected for aviation and realizing that he was too isolated to be more than a mere curiosity where he was, he immediately left for England.

John Duigan beside the Bleriot on left and E.N.V. powered Avro-Duigan Biplane on the right

To round off his story as quickly as possible, shortly after arriving, he bought one of the first Avro traction biplanes, and did a good deal of development work on it at the A. V. Roe establishment at Huntingdon. He obtained his license there, No 211. His Australian ticket, [obtained later], was No 21. He improved the Avro so much that he was unable to resist the tempting offers made for it, much to Father’s annoyance, as he had managed a short trip to England and expected to qualify for his license on it.

The brothers returned to Australia with an ENV engine, and managed to take sufficient time from the serious business of life to build another aeroplane at Grandfather’s house in Ivanhoe.

The brothers returned to Australia with an ENV engine, and managed to take sufficient time from the serious business of life to build another aeroplane at Grandfather’s house in Ivanhoe.

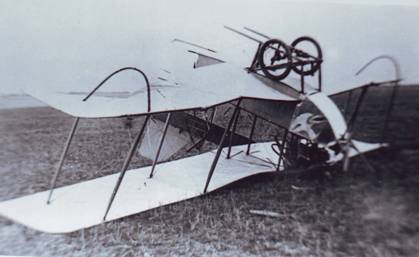

The 1912 Duigan Tractor Biplane, under construction in Ivanhoe

The 1912 Duigan Tractor Biplane, at Ivanhoe

This is virtually all A.V. Roe design, it shows how far the aeroplane had come in two short years. This machine was beautifully made and weighed a good deal less than the prototype. The seeds of disaster are the two loose looking wires emerging from the square hole underneath the rear cockpit. History of the time notes the Avro as the most advanced machine then flying, but indicates that it had one backward looking feature, warping. This was abandoned in due course and, incidentally, was the ancestor of the Avro trainer.

Perhaps the reason why wing warping was abandoned can be seen in the next photo, appropriately,

Perhaps the reason why wing warping was abandoned can be seen in the next photo, appropriately,

The 1912 Duigan Tractor Biplane, crashed in February 1913, at Keilor

This picture gives a good idea of the layout of the undercarriage. Other peoples prangs were always funny. At the time it must have been heart breaking. When tried out on straight flights the machine flew like a bird, but when a turn was tried , the bank continued to increase despite full opposite stick, the nose dropped and it hit the ground and turned a few cartwheels. Uncle Jack was bruised all over and though he did not break anything he was laid up for a long time. The reason for the crash seems to be, that the wing warping mechanism was not powerful enough. It must have been reasonably effective on the English models, because it had been in use for a year or so, and Uncle Jack had qualified on a similar machine. Anyway if he pioneered nothing else, he pioneered the abandonment of the wing warping.

This is just about the end of John Duigan, Pioneer, the remainder, is the story of a good many Australian Flyers. By the time he had recovered from the crash, he was married and had to set out to earn a living. Then came the War and service with the AFC, by the end of which he was desperately wounded. Eventually he made a complete recovery and when he returned to Australia there was a good deal more scope for electrical and mechanical engineers than there was for aviators. He lived out the remainder of his active life running his own firm “Old Bridge Motors” in Yarrawonga.

He died in Ringwood in July 1951.

Finally to sum up, John Duigan was a pioneer of Australian Aviation. To the extent that most pioneers are, he was a pioneer by chance, then opportunity coincided with his training and circumstances, but that in no way detracted from his achievement.

Apart from Hargrave one might say that he was the pioneer of Australian Aviation, if the phrase connotes original work by an Australian in Australia.

Now what sort of a pioneer was he by world standards? I don’t think he can truly be described as an inspired creator; his strength lay, mainly, in refining what had already been evolved in principle. For all that, he produced an extraordinary sensible aeroplane at a time when, one might say without being flippant, that all those in existence had some basically silly features.

He obviously did not do this by buying a blueprint. The mistakes he made at the outset, give some indication of the small amount of real information that he had to begin with. I think the speed at which he produced a successful aeroplane, and the fact that in a few years, all the ideas it embodied, appeared as common knowledge; have obscured the amount of original thinking that went into it’s production.

When he started he had an enormous advantage over the pioneers of the previous decade; he knew that flight of a sort had been achieved. Apart from that, I think that he had no more certain data than the Wrights, and more often than not he was ahead of what he received as he went along.

His work was parallel with, and anything between 6 months and a year behind what was going on in Europe, so it had virtually no effect at all on the development of aviation. But as a personal tour de force in all aspects of flying, I think it puts Uncle Jack up there with the leaders.

In one respect I think I can claim that he was ahead; that is that he never made any claims at all.

This is just about the end of John Duigan, Pioneer, the remainder, is the story of a good many Australian Flyers. By the time he had recovered from the crash, he was married and had to set out to earn a living. Then came the War and service with the AFC, by the end of which he was desperately wounded. Eventually he made a complete recovery and when he returned to Australia there was a good deal more scope for electrical and mechanical engineers than there was for aviators. He lived out the remainder of his active life running his own firm “Old Bridge Motors” in Yarrawonga.

He died in Ringwood in July 1951.

Finally to sum up, John Duigan was a pioneer of Australian Aviation. To the extent that most pioneers are, he was a pioneer by chance, then opportunity coincided with his training and circumstances, but that in no way detracted from his achievement.

Apart from Hargrave one might say that he was the pioneer of Australian Aviation, if the phrase connotes original work by an Australian in Australia.

Now what sort of a pioneer was he by world standards? I don’t think he can truly be described as an inspired creator; his strength lay, mainly, in refining what had already been evolved in principle. For all that, he produced an extraordinary sensible aeroplane at a time when, one might say without being flippant, that all those in existence had some basically silly features.

He obviously did not do this by buying a blueprint. The mistakes he made at the outset, give some indication of the small amount of real information that he had to begin with. I think the speed at which he produced a successful aeroplane, and the fact that in a few years, all the ideas it embodied, appeared as common knowledge; have obscured the amount of original thinking that went into it’s production.

When he started he had an enormous advantage over the pioneers of the previous decade; he knew that flight of a sort had been achieved. Apart from that, I think that he had no more certain data than the Wrights, and more often than not he was ahead of what he received as he went along.

His work was parallel with, and anything between 6 months and a year behind what was going on in Europe, so it had virtually no effect at all on the development of aviation. But as a personal tour de force in all aspects of flying, I think it puts Uncle Jack up there with the leaders.

In one respect I think I can claim that he was ahead; that is that he never made any claims at all.